If Looks Could Kill …The Art of the Female Gaze by Agnes Fanning

- Agnes Fanning

- Oct 26, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: Jan 8, 2021

“Would that be dangerous, to not look while being looked at?”

― Helen Oyeyemi, The Icarus Girl

According to Greek mythology, those who gazed into Medusa’s eyes would turn to stone. But what changes if, instead, we say that Medusa possessed the ability to turn anyone she gazed at to stone? The question lies in establishing the difference between what it means to see and what it means to look. ‘To see’ can be defined as noticing or becoming aware or someone or something, whereas ‘to look’ is to direct your gaze in a specified direction. Looking is an active movement that requires intent, as opposed to the passive process of seeing.

This distinction is important because it allows us to reframe the space that Medusa occupies in classical mythology. The story goes that, after being raped by Poseidon, the beautiful Medusa is the one that receives the punishment; Athena turns her into a monstrous Gorgon, with snakes for hair and a deadly gaze. She is feared and seen as a hideous threat. However, if you have to gaze into her eyes – in other words, make eye contact with her – to be petrified, you don’t turn to stone because you see or looked at her, you turn to stone because she looked at you. In a world were women are judged by their appearance, routinely acknowledged as objects to be seen and bodies to be looked at, Medusa’s fatal gaze can be redefined as an act of defiance rather than one of defence. All the men that come before Perseus, the ‘hero’ who beheads her, don’t die because her appearance is so horrific to lay eyes on, rather Medusa kills them because she reverses the action of the male gaze, confronting it with the female gaze. To quote the feminist French director and artist Agnès Varda:‘The first feminist gesture is to say: “OK, they’re looking at me. But I’m looking at them.” The act of deciding to look, of deciding that the world is not defined by how people see me, but how I see them.’

An interesting inversion of the myth of Medusa and Perseus is the Old Testament story of Judith and Holofernes. The same action takes place, but in the latter, it is the female who beheads the male. The

Bible tells the story of Judith, described as a beautiful widow, who seduces and subsequently slays Holofernes, a general sent to attack her home city. Throughout history, this story has been turned into art, and you only have to look at modern depictions to see how Judith has become the subject of male

fantasies (see Franz Stuck’s Judith (1928)). To what extent can a woman be depicted as empowered by her sexuality if she is a product of the male gaze? Do we look at Gustav Klimt’s Judith I differently to Tina Blondell’s I’ll make you shorter by a head (Judith I)?

(Left: Judith I (1901) - Gustav Klimt, Right: I’ll make you shorter by a head (Judith I) (1999) - Tina Blondell)

Referring to her reworking of Klimt’s Judith, Blondell (born 1953) has said: ‘I believe that Klimt painted Judith the seductress. I wanted to paint Judith the executioner.’ Almost four hundred years earlier, Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1656) was doing something similar. One of the few female artists from the seventeenth century that has received the recognition she deserves today, Artemisia also painted perhaps the most well-known depiction of Judith slaying Holofernes. She produced various different paintings inspired by the biblical story, another being Judith and her Maidservant, painted after a similar one by her father, also an artist. Although they portray the same moment of the story, the slight differences illustrate how depiction varies depending on whether the same subject is represented through the male or female gaze.

Left: Judith and her Maidservant (c.1613-14) - Artemisia Gentileschi, Right: Judith and her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes (c.1608) - Orazio Gentileschi)

Both paintings reproduce the same moment following the narrative’s main action; the women are checking to see if anyone has caught them. In her father’s more idealised style, Holofernes’ head is at the centre of the composition and Judith’s sword is hardly visible as she holds it by her side. By contrast, Artemisia’s painting places less emphasis on the grey and lifeless severed head. Instead, by painting Judith’s bold stance with the sword gripped over her shoulder, she becomes a self-assertive protagonist.

The male gaze – defined as the perspective of a notionally typical heterosexual man considered as embodied in the audience or intended audience for films and other visual media, characterized by a tendency to objectify or sexualize women – overwhelmingly determines how women are portrayed and therefore seen. Like in the case of Artemisia, the worth of a woman is established in terms of men, and recently there has been a move away from solely seeing her art through the lens of her biography and through the men that featured as part of it.

Until recently, I felt like my body wasn’t mine

If the worth of a woman is established in terms of men, it is also established in terms of how she is seen by men. This objectification and idealisation leads to girls growing up, seeking validation from the male gaze. Until recently, I felt like my body wasn’t mine, like it had been appropriated by society for the purpose of reflecting its normative standards. I wanted to be seen how society wanted to see me. It’s easy to feel as though the way I see myself is completely divorced from how I think people see me and it’s also easy to decide to change who you are to try and determine how people see you. An idea exists of wanting to be a certain way because it’s easier and less confusing. Consistency is palatable in a conformist society.

However, it would be wrong to convey a simplified binary view of the world we live it. It isn’t reflective of society. Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw, a civil rights activist and legal scholar, coined the term ‘intersectionality’ in an academic paper written in 1989 (“Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex.”). The term acknowledges that discrimination relating to gender equality varies depending on other aspects of a woman’s identity: age, race, ethnicity, class, religion. Crenshaw argued that traditional feminism excluded black women due to their unique experience in facing overlapping discrimination.

A contemporary American artist who examines the intersectionality of race, gender, and sexuality is Tschabalala Self (born 1990). Her aim is to provide an explanation of the voyeuristic tendencies towards the gendered and racialized body.

(Left: Out of Body (2020) - Tschabalala Self, Right: Carma (2016) - Tschabalala Self)

In her art, Self exaggerates the physical characteristics of the black female body to draw attention to the way the black female form is seen. She states that the figures in her work ‘are fully aware of their conspicuousness and are unmoved by the viewer. Their role is not to show, explain, or perform but rather “to be.” In being, their presence is acknowledged and their significance felt.’ The gaze of the figure in Carma directly confronts the viewer, forcing us to consider how our own conscious or unconscious biases affect the way we look at her. The viewer is made complicit in the act of looking from the perspective of the voyeur and challenged by the figure:

if she is going to be looked at, it’ll be on her terms.

It’s interesting to consider that art extends itself to any form of representation; how we see women in art is how we see women presented in the media, for example. In the same way, humans exhibit themselves like we exhibit art – the images we post are there to be looked at. In these spaces, women are still seen as objects of desire and in art history this is exemplified by the tradition of the female nude, whereby the female naked body was presented as an object to satisfy a man’s gaze. Increasingly, this has been called into question, and one woman that reverses the gendered portrayals of the nude is the Welsh artist Sylvia Sleigh (1916-2010).

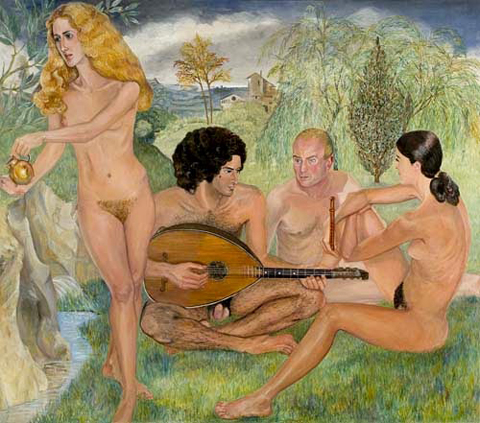

(Left: Le Concert Champêtre (c.1509) - Titian, Right: Concert Champêtre (1976) - Sylvia Sleigh)

Her work subverts this form of painting by depicting nude men in poses that were historically ascribed to women, subjecting nude men to the male gaze. She also equalizes the roles of men and women. For example, in the painting above she repaints Titian’s work, portraying all the figures as nudes, rather than just the women. Sleigh has affirmed that ‘I feel that my paintings stress the equality of men and women (women and men). To me, women were often portrayed as sex objects in humiliating poses. I wanted to give my perspective.’

Challenging the way women are seen in art, and by extension society, makes us challenge the way we see women/ourselves. I’m 22 now and I can feel myself becoming self-aware, regarding how I perceive my identity, and critical of the structures that influence the way I am seen. A big part of this is acknowledging that my own experience of the male gaze and finding my female gaze has been made significantly easier by being white and cisgender. The female gaze confronts norms imposed by hegemonic masculinity (a practice that legitimizes men's dominant position in society), but this is not to say that women are the only ones affected by it. Views on gender held by society can be as damaging to men as they are to women, and even then, gender should not be confined to simply refer to male and female.

In art, as in reality, the female gaze holds immense power, and after being obscured by misogyny,

‘you only have to look at the Medusa straight on to see her. And she's not deadly. She's beautiful and she's laughing.’ (Hélène Cixous, ‘The Laugh of the Medusa’).

Inspiring! I love the mix of classical art and myths with more current pieces